A new look into the Whirlpool Versión en español

The Spanish poet José Hierro, when presenting his book Cuaderno de Nueva York (“New York Notebook”), said that any major poet has to write about both New York and spring, at least once in a lifetime. The same could be said about M51, the Whirlpool Galaxy, in the context of astronomical imaging. Every relevant collection of astronomical photographs has to include this object at least once, if not more times, and every new look to this magnificent object reveals different aspects of this grand-design spiral galaxy.

Galaxy M51 was discovered by Charles Messier in 1773, but its outstanding spiral structure was first perceived by William Parsons (Earl of Rosse) in 1845, using his huge reflecting telescope, the Leviathan of Parsonstown. A large telescope is needed to see its intricate shape, but even small amateur telescopes reveal that this galaxy is not isolated, but has a small companion, the dwarf irregular galaxy NGC 5195.

Now it is clear that these two stellar systems are colliding and that the outstanding spiral shape of M51 is due, mainly, to the tidal forces unleashed during this process. Just by chance, we see the disk of M51 face on from Earth, what allows studying it in detail. At a distance of 23 millions of light-years, the apparent dimensions of M51 mean that that galaxy has to be quite similar to our own, yet somewhat smaller.

M51 and its companion are performing a cosmic dance that, during the last 500 million years has made NGC 5195 pass twice through the disk of M51. Now, the small galaxy is located slightly behind the disc of the Whirlpool, and moving away from us.

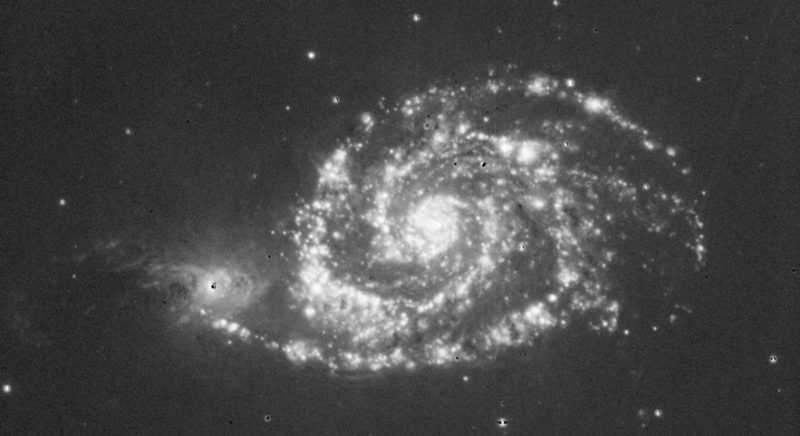

M51: H-alpha enhanced. 35 hours of integration through the Zeiss 1.23 m telescope of Calar Alto Observatory equipped with a research-grade CCD camera and a set of photographic RGB filters by Baader Planetarium (24 hours), and a Baader Planetarium interferometric H-alpha filter (7 nm passband, 11 additional hours). The H-alpha emission in this image has been enhanced by a factor 4, to highlight the star-forming regions in the disk of M51 and other HII extensions around NGC 5195. Field of view of 15 arcminutes (one quarter of the apparent width of the full Moon). North left, East down.

The interaction of both galaxies induces a bunch of collateral effects, being the spiral structure of the main galaxy only one of them. When galaxies collide, their stars do not crash ones against the others. Instead, they suffer strong alterations in their trajectories, what usually implies that many of them are expelled into the intergalactic space. This has happened to many stars from the secondary galaxy: streams of stars stripped of from NGC 5195 extend over the left (north) part of the image as a fuzzy fog. Many of the worlds in that area are doomed to get lost into the emptiness of space, as they move far away from their parent galaxies.

The gaseous content of colliding galaxies gets compressed and this triggers violent bursts of star formation (starbursts). Star forming regions can be detected thanks to the pinkish glow of ionised hydrogen. Images taken in the so-called H-alpha colour reveal where the gas is ionised by newborn stars. For this reason, we offer the M51 image in two versions: true colour and H-alpha enhanced.

The image

The image is the result of 24 hours of integration time with the Zeiss 1.23 m reflector of Calar Alto Observatory, equipped with a research-grade CCD camera ar a set of photographic RGB filters from Baader Planetarium. The true-colour image is the result from these filters, that reprooduce the chromatic sensitivity of the human eye. The final colour balance was decided considering as white the total sum of the light coming from the two galaxies. This way, the contrast among the different stellar populations in the field is more obvious. Particularly, the spiral galaxy exhibits bluish hues due to the massive, young and hot stars that populate its disk. This contrasts with the yellowish colours in the satellite galaxy, coming from lighter, older and colder stars.

M51: true colour. 24 hours of integration through the Zeiss 1.23 m telescope of Calar Alto Observatory equipped with a research-grade CCD camera and a set of photographic RGB filters by Baader Planetarium. Final colour balance done assigning white hue to the integrated light coming from the two large galaxies. Field of view of 15 arcminutes (one quarter of the apparent width of the full Moon). North left, East down.

The H-alpha enhanced image required a total of 35 hours of integration time with the 1.23 m Zeiss reflector of Calar Alto Observatory. Eleven additional hours are included through an interferometric H-alpha filter from Baader Planetarium. The H-alpha emission has been multiplied by a factor four to enhance the star-forming regions in the disk of M51, and other HII extensions around NGC 5195 as well.

M51 displays a star-forming activity much stronger than isolated galaxies like our own. This fact is highlighted in the H-alpha-enhanced image. As could be expected, star-forming activity closely follows the areas where younger and more massive stars are seen: the bluish spiral arms. But H-alpha emissions in M51 are not restricted to the spiral arms, but extend also into other areas. One of the most outstanding and intriguing features of this image is the fuzzy region of faint H-alpha emission to the north (left) of NGC 5195, a detail seldom seen before and closely related, too, to the effects of the collision on the gaseous content of these galaxies.

Many of the tiny points in the image are stars belonging to our own Galaxy. But a detailed inspection reveals that most of the small spots are other background galaxies. Small and remote extragalactic systems, of many shapes and colours, can be seen down to the edge of infinity in this photo. The two most outstanding background galaxies are the bright edge-on spiral galaxy IC 4277 seen close to the lower left (north-east) corner of the frame, and the small irregular galaxy IC 4278, to the right of the previous one, below (east) from the bridge of stars that seems to link M51 with NGC 5195.

This image has been obtained with the Zeiss 1.23 m reflector of Calar Alto Observatory as a part of the public outreach Project conducted by Foundation Descubre with this instrument. The observations have been planned and carried out by the Documentary School of Astrophotography (DSA), and the data have been processed by this organisation with the collaboration of the Astronomical Observatory of the University of Valencia (OAUV), using the software package PixInsight.

Image download

Image credits: Calar Alto Observatory, Descubre, DSA, OAUV. Vicent Peris (OAUV/DSA/PixInsight), Jack Harvey (SSRO/DSA), Steven Mazlin (SSRO/DSA), Carlos Sonnenstein (Valkànik/DSA) and Juan Conejero (PixInsight/DSA)

Spiral galaxy M51, true colour

Spiral galaxy M51, H-alpha enhanced

Only H-alpha, monocrhomatic image of M51

Additional information

Astronomy Picture of the Day (APOD), 2010 June 11th

By David Galadí Enríquez